Part A

Introduction

A holistic patient care plan is a multifaceted process often involving professionals from different disciplines; particularly in a mental care word there are multiple cases that also present with comorbidities, requiring services from a multidisciplinary team of professionals. The existence of a hierarchical structure within such organisational settings is inevitable and often deals with interprofessional conflict (Busari et al., 2017). Contemporary literature suggests that effective team working and collaboration is extremely important to achieve patient outcomes and ensure patient safety in the healthcare environment (Jackson et al., 2001; Ubaidi, 2020). Interprofessional collaboration within a healthcare environment is defined as the practice in which people are professionals belonging to different specialties come together to devise a care plan for a patient with acute or complex care needs. Interprofessional collaboration is also affected by multiple human factors which may include stress, prejudice communication, hierarchical structure, and conflict resolution (Leonard et al., 2004; Paradis & Whitehead, 2015). Contact Theory is an important piece of literature to study the role of communication and other human factors to build interprofessional collaboration (Leonard et al., 2004). This assignment will particularly discuss three human factors of communication, Prejudice and teamwork to deliver patient safety and health outcomes. The second part of the work will deal with personal reflection using Gibbs model of reflection to identify future room for improvement.

Critical Discussion

In a multi professional team, it is very important to be able to communicate the ideas and concerns as effectively as possible. While open communication has been suggested as an obvious answer literature argues in favor of a closed loop communication system. Resource Management Strategy adopted in the aviation industry can be used as an example to curtail accidents that arise from communication failures between crew members (Leonard et al., 2004). The crew resource management concept in the aviation industry has been used to set communication protocols and effective teamwork. In 2000 Leonard et al., (2004) executed a planned study involving 12 clinical teams that were subjected to a three-day intensive training regime about human factors by adopting trends and practices from the aviation industry to apply to high-risk medical environments (Leonard et al., 2004). All the right safety and confidential agreements were obtained to execute this study and the results obtained to be employed from managing complex healthcare situations are now collectively constituted as SBAR (situation, background, assessment, and recommendation). This study also highlighted that different healthcare professionals such as physicians and nurses are trained to communicate in different ways (Babiker et al., 2014; Cahn, 2020; Leonard et al., 2004). There is a fundamental difference between critical language, education, appropriate assertion, and experiences in different clinical areas between physicians and nurses (Marshall & Flanagan, 2010; Taberna et al., 2020). For example, the nurses are usually required to give an objective account of the severity of a patient’s condition in order to convince a physician but because of the differences in their communication styles, which basically require the nurses to be concise and cogent regarding the patient’s condition and then requiring the physician or surgeon to devise an urgent treatment intervention, compromises patient safety and is tantamount to hazard (Lingard et al., 2012; Taberna et al., 2020; Thistlethwaite, 2015). The practice of debriefing entails meeting with the entire team at the end of the day to reflect on the day’s challenges and positive outcomes to better practice in the future. This practice is recognized as one of the most important success factors within a surgical team and among multidisciplinary professionals (Catchpole et al., 2010; Marshall & Flanagan, 2010). The briefing also has its negative outcomes such as hiding or masking gaps and knowledge, reinforcing any professional conflicts and divisions as well as disruption of positive communication and perpetuation of a problematic overall culture there are multiple types of deep briefing that can be employed in a training setting such as audio-visual based self-lead and led by an instructor. Overall, debriefing can be used as an effective method of reflection in a healthcare setting (Leonard et al., 2004; Lingard et al., 2012).

The importance of team working in healthcare settings is unchallenged in contemporary literature. Multiple interventions, however, have been proposed in literature to improve team effectiveness. Two of these interventions: the CRM; crew resource management and TeamSTEPPS; Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety, are particularly distinguished. Both of these strategies are centered on personnel training (Leonard et al., 2004; Noyes, 2021). Other types of interventions include organizational redesign and a program which is a combination of training tools and organizational redesign. All these interventions are focused on improving functional performance and efficiency of the team as well as designing structures to motivate and incentivize overall team functioning within a hospital care setting. TeamSTEPPS is a step up from the conventional CRM program it is based on promoting 5 domains of competencies which include the overall structure of team management and leadership, communication, situational monitoring, and collective support (Catchpole et al., 2010; Marshall & Flanagan, 2010; Noel et al., 2022). This mode of training primarily focuses on coaching, measurement, change management, and implementation of the advised and recommended solutions. but it is important to consider that this training is susceptible to change depending on different healthcare environments and can be tailored to suit specific situational contexts. It also allows the opportunity to monitor and control both technical and non-technical skills (Catchpole et al., 2010; Prineas et al., 2021). Many studies have also promoted the implementation of simulation-based training which helps to artificially contrive real patient experiences which can help to replicate important and crucial aspects of a real time situation to allow interactive training. All these methods in various capacities have been deemed suitable to improve team working in a multidisciplinary team. they can not only be used to improve effectiveness but can also identify the areas which need improvement (Marshall & Flanagan, 2010; Prineas et al., 2021).

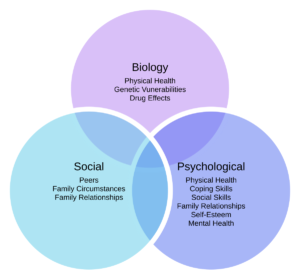

There have been multiple accounts of Prejudice within a healthcare setting which threatened patient safety and health outcomes (Baby, 2018). The Prejudice could be because of professional jealousy, a self-perceived sense of negative competition, racial and cultural differences (Dang et al., 2017; Jackson et al., 2001). While technical knowledge and acumen are important to achieve patient outcomes, interprofessional education and cultural competency is also important to bring about an efficient collaborative practice (Hassen et al., 2021; Vaismoradi et al., 2022). Conflict in opinion is widely observed in multidisciplinary professionals, particularly for patients with complex care needs. In these situations, a professional may feel undermined or disrespected. In order to manage this conflict, it is important for all the professionals to reflect critically on their own position within the team and focus only on achieving patient outcomes (Beacon, 2015; Jasemi et al., 2017).

With the evolution of healthcare in the last century, the complexity of the profession has increased to the point where more than 500 different healthcare professionals work in each major hospital. For holistic healthcare, there is a need for constant collaboration between these various professionals. To improve teamwork, the concept of Multidisciplinary Training (MDT) comes into play with the benefits of better communication and understanding. MDT improves collaboration so that the healthcare professionals could interact mutually to solve problems and to achieve the desired health outcomes. While this is beneficial to the patients, this synergy could be problematic to achieve. First, the philosophies around ethics could vary between healthcare professionals. They could either be cure-oriented or public health/social health oriented. Second, there are often uneven power relations between professionals of different specialties, which hamper effective collaboration. And thirdly, professionals of one discipline are less likely to accept the professionals from other disciplines because of conventional ideals or varying social identities.

As evident, the role of human factors in influencing inter-professional collaboration is unparalleled. It is, therefore, pivotal for healthcare professionals in charge of complex care needs patients to be mindful of their attributes, behaviours and attitudes within a team. They should be able to communicate exactly the need of the hour, especially if it concerns a change in patient’s condition (Taberna et al., 2020; Ubaidi, 2020). It is also important for the professionals to avoid all sorts of conflict and Prejudice with the other members of the team. Conflict management within a healthcare setting can be dynamic and therefore difficult to manage if the hierarchy is autocratic and constricting(Beacon, 2015).

Conclusion

Effective team collaboration is important to achieve patient health and safety outcomes. The role of human factors in breaking or reinforcing collaboration cannot be neglected. Contemporary literature proposed multiple strategies and interventions to promote collaboration in acute or complex healthcare settings. Communication, Teamworking and avoiding Prejudice hold primary importance in achieving this objective. The role of simulation-based exercises is also unprecedented in training professionals from different specialties to practice collaboration and coordination.

Part B

Reflection

This module evidenced that effective inter-professional team collaboration is of pivotal importance in a multidisciplinary healthcare team. It allows designing and providing a multifaceted treatment plan to the patient by ensuring that patient and carer empowerment is not compromised. I will reflect using Gibb’s reflective model, from experience within a mental health centered MDT, the importance of collaboration (Gibbs, 1988). I will also identify shortfalls in my performance and goals to remedy it in the future. Patient’s confidentiality will be maintained throughout this reflective exercise in accordance with the NMC code of conduct.

Description: Patient Sky was an 80-year-old African American diabetic woman diagnosed with Parkinson disorder. Her MDT comprised of a neurologic, nephrologist, diabetologist, a social worker, a mental health nurse and me as an assistant student nurse. Having lived through her fair share of racial discrimination, Sky was very sensitive to any direct or indirect reference to her racial identity. She also suffered from trust issues and would take all advice with a tinge of salt.

Feeling: An effective holistic treatment plan gives special importance to rapport building with the patient and their immediate carers or family members (Jasemi et al., 2017). It also ensures that the patient is part of the care planning process. I observed that patient Sky was always on the edge and had a hard time trusting her carers. Little effort was invested in developing her trust by talking to her by the specialists. I always noticed that when spoken to politely and heard, Sky would accept whatever was asked of her.

Evaluation: Contemporary literature emphasizes on building rapport with patients and convincing them about the designed treatment plan(Baby, 2018; Butt, 2021; Hassen et al., 2021; Jackson et al., 2001). This involves assuming the right posture to make the patient feel comfortable and allowing them to speak. Active listening is another important feature in rapport building. Moreover, a therapist belonging to the same racial background could have also helped calm the patient’s nerves. Sky’s tantrums could only be soothed by her son which created hurdles in the care process, especially medication.

Analysis: For an interprofessional collaboration to be efficient, it is essential that the patient is content with the treatment plan and is free from all doubts. All members of the MDT should avoid any obvious or covert behavior that might show any prejudice. Moreover, patient comfort during the care planning process should be of utmost priority (Jackson et al., 2001; Saint-Pierre et al., 2018).

Conclusion: Active listening for rapport building by all members of the MDT is very important for the care process to work efficiently. It is also important to make sure the patient is comfortable with the MDT and the care plan.

Action Plan

Specific: Improving my active listening and rapport building through simulation exercises.

Measurable: My ability to successfully build rapport with at least two patients every week will help in charting progress.

Achievable: My evidence based theoretical learning will help me during practical sessions.

Relevant: I have always found it difficult to stop talking during a conversation and allow others a chance to speak their mind. I also interject a lot.

Timebound: I will ensure participating in at least 6 simulation and real time exercises every month.

References

Babiker, A., el Husseini, M., al Nemri, A., al Frayh, A., al Juryyan, N., Faki, M. O., Assiri, A., al Saadi, M., Shaikh, F., al Zamil, F., Husseini, E. M., Neri, A. A., Frayh, A. A., Juryyan, A. N., Saadi, A. M., & Zamil, A. F. (2014). Health care professional development: Working as a team to improve patient care. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 14(2), 9. /pmc/articles/PMC4949805/

Baby, J. (2018). Equitable health: let’s stick together as we address global discrimination, Prejudice and stigma. Archives of Public Health, 76(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S13690-018-0291-3

Beacon, A. (2015). Practice-integrated care teams – Learning for a better future. Journal of Integrated Care, 23(2), 74–87. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICA-01-2015-0005

Busari, J. O., Moll, F. M., & Duits, A. J. (2017). Understanding the impact of interprofessional collaboration on the quality of care: a case report from a small-scale resource-limited health care environment. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 10, 227. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S140042

Butt, M. F. (2021). Approaches to building rapport with patients. Clinical Medicine, 21(6), e662. https://doi.org/10.7861/CLINMED.2021-0264

Cahn, P. S. (2020). How interprofessional collaborative practice can help dismantle systemic racism. Https://Doi.Org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1790224, 34(4), 431–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1790224

Catchpole, K. R., Dale, T. J., Hirst, D. G., Smith, J. P., & Giddings, T. A. E. B. (2010). A multicenter trial of aviation-style training for surgical teams. Journal of Patient Safety, 6(3), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0B013E3181F100EA

Dang, B. N., Westbrook, R. A., Njue, S. M., & Giordano, T. P. (2017). Building trust and rapport early in the new doctor-patient relationship: a longitudinal qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12909-017-0868-5/TABLES/1

Gibbs, G. (1988). A guide to teaching and learning methods. Learning by Doing, 129. https://books.google.com/books/about/Learning_by_Doing.html?id=z2CxAAAACAAJ

Hassen, N., Lofters, A., Michael, S., Mall, A., Pinto, A. D., & Rackal, J. (2021). Implementing Anti-Racism Interventions in Healthcare Settings: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, Vol. 18, Page 2993, 18(6), 2993. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH18062993

Jackson, J. L., Chamberlin, J., & Kroenke, K. (2001). Predictors of patient satisfaction. Soc Sci Med, 52(4), 609–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00164-7

Jasemi, M., Valizadeh, L., Zamanzadeh, V., & Keogh, B. (2017). A Concept Analysis of Holistic Care by Hybrid Model. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 23(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1075.197960

Leonard, M., Graham, S., & Bonacum, D. (2004). The human factor: The critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13(SUPPL. 1), i85–i90. https://doi.org/10.1136/QSHC.2004.010033

Lingard, L., Vanstone, M., Durrant, M., Fleming-Carroll, B., Lowe, M., Rashotte, J., Sinclair, L., & Tallett, S. (2012). Conflicting messages: examining the dynamics of leadership on interprofessional teams. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 87(12), 1762–1767. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0B013E318271FC82

Marshall, S. D., & Flanagan, B. (2010). Simulation-based education for building clinical teams. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma and Shock, 3(4), 360. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2700.70750

Noel, L., Chen, Q., Petruzzi, L. J., Phillips, F., Garay, R., Valdez, C., Aranda, M. P., & Jones, B. (2022). Interprofessional collaboration between social workers and community health workers to address health and mental health in the United States: A systematized review. Health & Social Care in the Community. https://doi.org/10.1111/HSC.14061

Noyes, A. L. (2021). Navigating the Hierarchy: Communicating Power Relationships in Collaborative Health Care Groups. Https://Doi.Org/10.1177/08933189211025737, 36(1), 62–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/08933189211025737

Paradis, E., & Whitehead, C. R. (2015). Louder than words: power and conflict in interprofessional education articles, 1954-2013. Medical Education, 49(4), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/MEDU.12668

Prineas, S., Mosier, K., Mirko, C., & Guicciardi, S. (2021). Non-technical Skills in Healthcare. Textbook of Patient Safety and Clinical Risk Management, 413–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59403-9_30

Saint-Pierre, C., Herskovic, V., & Sepúlveda, M. (2018). Multidisciplinary collaboration in primary care: a systematic review. Family Practice, 35(2), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1093/FAMPRA/CMX085

Taberna, M., Gil Moncayo, F., Jané-Salas, E., Antonio, M., Arribas, L., Vilajosana, E., Peralvez Torres, E., & Mesía, R. (2020). The Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) Approach and Quality of Care. Frontiers in Oncology, 10, 85. https://doi.org/10.3389/FONC.2020.00085

Thistlethwaite, J. (2015). Power and conflict in health care: everyone’s responsibility. Medical Education, 49(8), 847. https://doi.org/10.1111/MEDU.12757

Ubaidi, B. A. A. al. (2020). Workplace conflict in healthcare settings. Hamdan Medical Journal, 13(4), 186. https://doi.org/10.4103/HMJ.HMJ_25_20

Vaismoradi, M., Fredriksen Moe, C., Ursin, G., & Ingstad, K. (2022). Looking through racism in the nurse-patient relationship from the lens of culturally congruent care: A scoping review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(9), 2665–2677. https://doi.org/10.1111/JAN.15267