Part A

Introduction

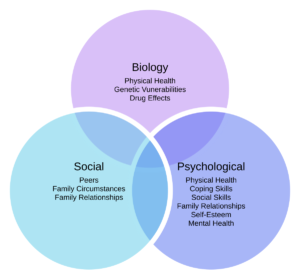

Quality care service provision in a mental health facility is dependent on interprofessional collaboration, which in turn is dependent on multiple human factors. Interprofessional collaboration is a practice where two professionals from different specialities must coordinate, converse and interact with the patient to deliver quality care (Cahn, 2020; Leonard et al., 2004). Within a hospital setting, “Communication” is unanimously agreed to be the core competency required for effective collaboration. Particularly for patients with complex care needs, it is important for the assigned multi-disciplinary team of professionals to be able to converse effectively and without bias. All prominent international literature, including the Romanow (2002) report, WHO documents, NHS documents, emphasize the importance of interprofessional collaboration (Cahn, 2020; Prentice et al., 2015). Human factors basically entail the science and understanding of people’s emotions, capabilities, capacities and performance at work. These factors, often referred to as ergonomics, help in minimizing human errors by accepting human limitations and strategizing corrective actions(Busari et al., 2017a). Using Contact theory, this work will highlight the importance of interprofessional collaboration and the influence of human factors on care service provision in mental health nursing. In the next section, I will use Gibb’s Model of reflection to identify my current learning standpoint and room for future improvement.

Critical discussion

Ever since the proposition of Contact Theory by Allport in 1954, which emphasizes on the benefits of contact in inter and intragroup proceedings, a lot of literature has evidenced its utility in reducing conflict and prejudice (Cullati et al., 2019; Paradis & Whitehead, 2015). These positive outcomes are not only observed within a specific group but also between different groups. It, therefore, helps in promoting both implicit and explicit conflict resolution. Patients with complex care needs often require dynamic care plans and flexible service, because of which Effective Team Working becomes, inevitably, a sine qua non. Within a mental health care setting, two types of barriers to effective team-working have been identified by Oflaz et al., (2019); barriers related to the organization and those centred around the individual. The latter includes negative inter-personal attitudes and behaviors such as avoiding responsibilities, trivializing contributions from other team members, preferring to work in isolation and lacking essential skills of collaboration. For example, when a task needs doing, instead of asserting superiority by suggesting some other team member does it, the professionals should take the initiative and work for the patient’s benefit (Busari et al., 2017b, 2017a). It is also important to establish democratic and active leadership strategies in a multi-disciplinary team. Designing new well-structured communication strategies such as closed communication, callouts, active listening, using assertive and common language and regular debriefing can help develop mutual trust and reduce hierarchy’s negative impact (Noyes, 2021).

Lack of Communication in a multi-disciplinary setting is another important human factor which threatens the quality-of-care service provision (Lingard et al., 2012; Renfro et al., 2018). This can either be because of language and cultural barriers or due to a self-perceived personal professional superiority. It is also perceived that conflicts in healthcare settings usually occur because of interprofessional misunderstandings, different approaches to solving a problem, and different accountability practices as well as a lack of proper proactive leadership or any possible imbalance of power that could breed prejudice and bias in leadership (Gergerich et al., 2019; Noyes, 2021). This lack of communication was particularly evident in a rigid hierarchical structure which reduces the capability of group cohesion and instead causes conflict, particularly between physicians and nursing technicians. Moreover, a rigid structure and lack of democratic communication also creates conflict and depreciates consensual and collaborative working among professionals (Gergerich et al., 2019; Noyes, 2021). According to the Contact theory to achieve an effective collaborative outcome it is important for the interaction to be free from personal perceptive and behavioral bias. The contact is successfully generalized if this bias is reduced not only towards a particular colleague but also towards general outgroups. This generalization of the positive effect of contact helps in extending collaboration not only among the multi-disciplinary healthcare team but also towards patients belonging to different cultural, racial, and linguistic backgrounds (Babiker et al., 2014).

Care provision for patients with common mental health problems is often complicated, because it requires care provided by a multi-disciplinary team which in most cases includes nursing professionals, social care experts, occupational health, and psychiatric help. In these cases, the NHS (2012) recommends an Impact model which includes participation of the service users, their families and healthcare professionals belonging to different specialities (Dang et al., 2017; Jackson et al., 2001; Mohammed et al., 2022) . The aim is to make a stepped care model depending on the changing needs and dynamic responses to the initial treatment plan. According to this 3-Step Model, the care plan is initially designed by qualified and expert case managers and care navigators, who were responsible for coordinating the program. In the first step, a general practitioner aided by a psychology therapist will help in signposting and implementing a particular well-being plan. In Step 2, recommendations will be made for psychosocial and emotional programs, which would include community initiatives, individualized treatment plans or self-help options, involving social support professionals (NHS, 2012). The final step 3 involved face to face session with a senior clinical expert member, which included medication treatment, accompanied supervision from nursing specialists, and psychological interventions. Step 3 was particularly for people with chronic and rapidly deteriorating mental health problems (NHS, 2012). This Model showed significant clinical improvements by improving coordination among different professionals by employing them in different stages of care. It also ensured that the service user was actively involved in developing a need-based flexible care plan (Noel et al., 2022; Thistlethwaite, 2015).

Keeping Service Users Updated about changes in their health conditions and, consequently any modifications in the treatment plan helps to inculcate confidence, trust and improves self-esteem. For patients with cognitive impairments and complex care needs, this is particularly important. In most cases, when a patient presents with an acute medical condition, comorbidities are often ignored or overlooked. Most of these conditions are mental health problems such as anxiety, depression and cognitive decline (Babiker et al., 2014; Gergerich et al., 2019). Employing a well-coordinated multi-disciplinary team can help in providing a multi-faceted treatment plan at different stages. Effective rapport building with the patient can help facilitate closed-loop communication within the team and maintain confidentiality while also ensuring the care provision team is aware of information critical to patient safety and health outcomes (Lingard et al., 2012; Renfro et al., 2018).

In case of internal conflict and lack of coordination, patient safety and health outcomes are severely compromised. In a healthcare setting, workplace conflicts are particularly frequent contemporary literature evidence that a huge majority of healthcare professionals have witnessed in their practice disruptive behaviors and conflicts at least on a weekly basis if not daily 43% of these reported conflicts were about post-operative care between surgeons and intensivists (Butt, 2021; Ubaidi, 2020; van Keer et al., 2015). These conflicts often involved profanity, blaming, aggressive behaviors, and disagreements which significantly impaired communication and trust between the team members leading not only to poor mental health of the professionals themselves but also distracting their attention away from the patient outcomes and threatening the overall safety of the work environment. Contemporary literature also emphasizes on the role played by Hierarchical Power Structure which is frequently challenged by ongoing interprofessional care practices; multiple studies have also emphasized on this crucial correlation between hierarchical differences and workplace conflict (Dang et al., 2017; Ubaidi, 2020). These may occur between professionals from different specialities, within the same speciality, and at different stages of hierarchy.

Conclusion

While the contemporary trend in the medical practice is competency-based medical training, it still must seamlessly align not only with the community’s healthcare needs but also with the dynamics of organizational culture. According to the above discussion, patient safety and health outcomes are particularly dependent on effective team collaboration which in turn is dependent on multiple human factors such as the ability to communicate working without prejudice, to collaborate and work within a team towards mutual objectives, as well as being able to contribute without inflicting conflict. It is also important to highlight the inevitability of the role played by human factors in the provision of quality care service. As these factors cannot be ignored, it is, therefore, pivotal to recognize and acknowledge their existence and strategize patient care, particularly those with complex care needs, to circumvent any chances of neglect conflict or quality compromise that might be a resultant thereof.

Part B

Reflection

The evidence-based approach adopted in this module helped me to understand the importance of non-technical skills and human factors in achieving patient health and safety outcomes. I will use Gibb’s Reflective Model to recount and analyze from my own personal experience the importance of interprofessional collaboration in a mental health setting (Gibbs, 1988). In accordance with the NMC code of conduct, patient’s identity will be kept confidential.

Description: Patient Green was a 70-year-old Caucasian female, diagnosed with Dementia, cardiovascular complications and paralysis from the waist below. She was unable to function without support and required supervision. Her MDT comprised of a general practitioner, a neurologist, a cardiovascular specialist, me as a nursing mental health student assisting a nursing supervisor, and a social worker. Mrs. Green’s daughter was also involved in the care plan. Mrs. Green complained of severe backpain and sores. The social care worker did not report it to the team and trivialized the complaint. After a few days the pain became unbearable for Mrs. Green, and she was admitted to the hospital, where it was found that she had a herniated disk which needed microdiskectomy.

Feelings: As a part of the MDT, my responsibility was to observe, learn and report any ambiguities in the care process. It is very important for all members of the MDT to timely report any changes in patient’s condition. I felt that it was the responsibility of the social worker to report when the patient first started complaining of her back pain. Sores develop when the patient’s position has not been changed. As it was the responsibility of the daughter, being the immediate carer, to make sure Mrs. Green was comfortable, she should have reported the sores as well. I felt that there was a lack of coordination between the team members which resulted in discomfort for the patient.

Evaluation: It is important for the MDT to make sure family and immediate carers are debriefed regularly about the patient’s immediate needs. It became apparent that the daughter was not aware that this situation could arise and ignored early signs because of lack of awareness. Moreover, the social worker also, initially, trivialized the complaints. The concept of debriefing and regular updates requires the members to report both minor and major observations that could deter patient recovery.

Analysis: As an observer, the human factor of communication requires significant mention in this case. The social worker was hesitant to communicate to the specialists because of perceived hierarchical authority. This resulted in lack of coordination and hazard to patient safety.

Conclusions

Interprofessional collaboration in a multi-disciplinary team for complex care needs patients can only be successful if all members can communicate easily without being hindered by authority pretenses. All complaints must be clearly communicated.

Action Plan

Specific: Improving my communication skills.

Measurable: I will participate in at least two simulation-based training exercises biannually

Achievable: I already have the opportunity to learn from an MDT so I know the flaws in my communication

Relevant: I have always been passionate about making my accent easily understandable.

Time-dependent: I will enroll in more courses and multiple training exercises by the end of a two-year period.

References

Babiker, A., el Husseini, M., al Nemri, A., al Frayh, A., al Juryyan, N., Faki, M. O., Assiri, A., al Saadi, M., Shaikh, F., al Zamil, F., Husseini, E. M., Neri, A. A., Frayh, A. A., Juryyan, A. N., Saadi, A. M., & Zamil, A. F. (2014). Health care professional development: Working as a team to improve patient care. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 14(2), 9. /pmc/articles/PMC4949805/

Busari, J. O., Moll, F. M., & Duits, A. J. (2017a). Understanding the impact of interprofessional collaboration on the quality of care: a case report from a small-scale resource-limited health care environment. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 10, 227. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S140042

Busari, J. O., Moll, F. M., & Duits, A. J. (2017b). Understanding the impact of interprofessional collaboration on the quality of care: a case report from a small-scale resource-limited health care environment. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 10, 227. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S140042

Butt, M. F. (2021). Approaches to building rapport with patients. Clinical Medicine, 21(6), e662. https://doi.org/10.7861/CLINMED.2021-0264

Cahn, P. S. (2020). How interprofessional collaborative practice can help dismantle systemic racism. Https://Doi.Org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1790224, 34(4), 431–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1790224

Cullati, S., Bochatay, N., Maître, F., Laroche, T., Muller-Juge, V., Blondon, K. S., Perron, N. J., Bajwa, N. M., Vu, N. V., Kim, S., Savoldelli, G. L., Hudelson, P., Chopard, P., & Nendaz, M. R. (2019). When Team Conflicts Threaten Quality of Care: A Study of Health Care Professionals’ Experiences and Perceptions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes, 3(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MAYOCPIQO.2018.11.003

Dang, B. N., Westbrook, R. A., Njue, S. M., & Giordano, T. P. (2017). Building trust and rapport early in the new doctor-patient relationship: a longitudinal qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12909-017-0868-5/TABLES/1

Gergerich, E., Boland, D., & Scott, M. A. (2019). Hierarchies in interprofessional training. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 33(5), 528–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1538110

Gibbs, G. (1988). A guide to teaching and learning methods. Learning by Doing, 129. https://books.google.com/books/about/Learning_by_Doing.html?id=z2CxAAAACAAJ

Jackson, J. L., Chamberlin, J., & Kroenke, K. (2001). Predictors of patient satisfaction. Soc Sci Med, 52(4), 609–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00164-7

Leonard, M., Graham, S., & Bonacum, D. (2004). The human factor: The critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13(SUPPL. 1), i85–i90. https://doi.org/10.1136/QSHC.2004.010033

Lingard, L., Vanstone, M., Durrant, M., Fleming-Carroll, B., Lowe, M., Rashotte, J., Sinclair, L., & Tallett, S. (2012). Conflicting messages: examining the dynamics of leadership on interprofessional teams. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 87(12), 1762–1767. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0B013E318271FC82

Mohammed, E. N. A., Onavbavba, G., Wilson, D. O.-M., & Adigwe, O. P. (2022). Understanding the Nature and Sources of Conflict Among Healthcare Professionals in Nigeria: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 15, 1979–1995. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S374201

NHS (2012). Human Factors in Healthcare- A Concordant from the National Quality Board. PDF. Online. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/nqb-hum-fact-concord.pdf

Noel, L., Chen, Q., Petruzzi, L. J., Phillips, F., Garay, R., Valdez, C., Aranda, M. P., & Jones, B. (2022). Interprofessional collaboration between social workers and community health workers to address health and mental health in the United States: A systematized review. Health & Social Care in the Community. https://doi.org/10.1111/HSC.14061

Noyes, A. L. (2021). Navigating the Hierarchy: Communicating Power Relationships in Collaborative Health Care Groups. Https://Doi.Org/10.1177/08933189211025737, 36(1), 62–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/08933189211025737

Oflaz, F., Ancel, G., & Arslan, F., (2019). How to Achieve Effective Teamwork: The View of Mental Health Professionals. Cyprus Journal of Medical Sciences. 4(3): 235-41. 10.5152/cjms.2019.1009

Paradis, E., & Whitehead, C. R. (2015). Louder than words: power and conflict in interprofessional education articles, 1954-2013. Medical Education, 49(4), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/MEDU.12668

Prentice, D., Engel, J., Tapley, K., & Stobbe, K. (2015). Interprofessional Collaboration: The Experience of Nursing and Medical Students’ Interprofessional Education. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393614560566

Renfro, C. P., Ferreri, S., Barber, T. G., & Foley, S. (2018). Development of a Communication Strategy to Increase Interprofessional Collaboration in the Outpatient Setting. Pharmacy: Journal of Pharmacy Education and Practice, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/PHARMACY6010004

Thistlethwaite, J. (2015). Power and conflict in health care: everyone’s responsibility. Medical Education, 49(8), 847. https://doi.org/10.1111/MEDU.12757

Ubaidi, B. A. A. al. (2020). Workplace conflict in healthcare settings. Hamdan Medical Journal, 13(4), 186. https://doi.org/10.4103/HMJ.HMJ_25_20

van Keer, R. L., Deschepper, R., Francke, A. L., Huyghens, L., & Bilsen, J. (2015). Conflicts between healthcare professionals and families of a multi-ethnic patient population during critical care: An ethnographic study. Critical Care, 19(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13054-015-1158-4/METRICS