Contents

INTRODUCTION:

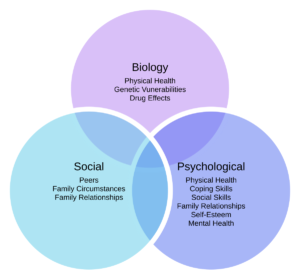

Article 38 of the International Court of Justice outlines treaties as one of the most important and primary sources of public international law. These treaties, in essence are the agreements between states that cover the matter of trade, human rights, invetments, armed conflict, sea and the natural resources.[1][2] In the course of dispute-resolution, international judges and arbitrators often deal with acts or decisions originating from other branches of international law. They must therefore determine the relevance of this external normative material in the proceedings they administer. The principle of comity advocates a standard of deference in such circumstances. Pursuant to this principle, which originates in the municipal context, courts and tribunals should make a deliberate attempt to take into account external legal sources in a bid to promote the coordination between the specialized regimes of international law, and prevent the conflicts and duplications which result from them operating in absolute isolation from each another. Although the substance and purpose of this principle are fairly uncontroversial, it has arguably no binding force at the international level.[3] As such it is imperative that the comparative study of the different sources of international and domestic law must be critically analysed to review the basis of judgements. The papers aims to analyse the provision relating to the dispute resolution process of the two forums; World Trade Organisation (WTO) and European Union (EU) legal system and analyse the key principles and efficiency of these systems.

DISCUSSION:

World Trade Organisation:

The WTO was formed with the objective of promoting international trade and promote international collaboration in foreign trade to remove the obstacles for cross-border movement of goods. It was formed with the enforcement of the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), on January 1, 1995, that expanded the scope of international trade liberalization. The principal new substantive obligations of the Uruguay Round were the liberalization of services, the incorporation of intellectual property rights, and the gradual deepening of agricultural reform. One of the most innovative features of the WTO is arguably its Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU).[4] The Appellate Body (AB) was introduced as a standing appeals tribunal that acted as the final arbiter for trade related dispute matters among its members. The decisions taken by the AB has changed the Government behaviour regarding trade matters and numerous practices have also been developed in the member states that contravene WTO rules. Although there are arguments on both sides for the performance and efficiency of the WTO and AB as a whole, some political scientist have plauded the rule-based and unbiased approach that is more closely related to legal principle than much of the international political system. A publication by Judith and Co.[5] claimed that “the WTO represents a victory for the legalists … (DSU) panel members construct their decisions with the assistance of a legal secretariat that helps them to resolve legal issues rather than to broker a political compromise.”[6]

The analysis of the interaction between three forums, the AB, the US and the EU can help formulate the three major characteristics which include strategic restraint or its lack in the choice of disputes filed by the potential complainants; strategic conciliation by the AB in matters involving powerful defendants; and strategic bargaining regarding the timing and terms of compliance by the losing defendants and winning complainants outside of the system of the DSU.

One of the matters of conservable concern is the enforcement of decision made by the WTO. This can be seen in the selection of cases that have put forward to the WTO for arbitration. One of the prime examples of such a case was the decision of the EU to withdraw its application against the US in relation to its Helms-Burton Act that concerned Cuba’s trade with third countries. THe cause for the withdrawal for the application was protect the WTO from being put in a contentious situation. EU had put forward the request for the establishment of the panel in the matter, but withdrew its application in the fear of delegitimizing the international arbiter body and proceedings that would damage the CSU position across the globe. The US could not justify its legislation on any legal grounds, but the White House had showed clear intention of renouncing any decision made against it which would have harmed the credibility of the WTO. In this way, the development and evolution of the WTO’s decision relies, in a great part, on the disputes that are put in front of it.

On the other hand of this situation are the situations where complicated and delicate issues are brought forward for the WTO to arbitrate. Such high stakes cases that decide on sensitive matters pose a significant risk to the future of the WTO due to the long-lasting effects it would have on the respect and credibility of the decision made therein. The important instance of the breakdown of this legal forbearance and restraint principle can be seen in the case of US – FSCs and EC – Beef Hormones. The problem arises when the defendant fails in its compliance of the DSU’s decision which undermines the authority of the AB.

Another cause of concern is the AB’s precedence of overruling the decision of the ad hoc panels that it hears, and most of the decisions are modified. A third of the cases that it heard in regard to the violation ruling have been partly or completely reverse by the Body while another fifth of the appeals have resulted in the Body modifying the basis for the decision made. As such, the AB has shown a biased approach while dealing with the matters involving powerful defendants which has resulted sharp alteration of the decisions made by many panels by interpreting the rules in a way that are beneficial to the powerful party. One such example may be seen in the cases involving the implementation of health and environment policies concerning the US and the EU. In such cases, the decisions of the AB have gone in detail to explain the ways that the same trade-restrictive policies could be implemented that would comply with the WTO guidelines. One more notable case of this instance is US – Shrimp and EC – Beef Hormones.[7]

Some of the legal scholars defend the reasoning and the decision made by the AB main body as the simple discourse of the judges clarifying the legal reasoning in the cases that were decided by the less experienced Ad hoc panels. However, this reasoning fails to account for the unjust and highly biased reasoning by the AB in favour of the powerful parties. As such, it is clear that the main proponent of decision-making is by the AB is its objective to seek compliance that would never undermine its own credibility. This is the reason that it tends to present the decision that are much more favourable to powerful party by tilting its stance in their favour in scope of the legal principles to develop a less onerous obligation. Even though, the AB seeks to present consistency and impartiality in its decision, the framing of its rule allow multiple interpretation that provides the AB sufficient room for flexibility to favour strategic conciliation.

Another issue with the framework adopted by the WTO is the lengthy compliance phase in its dispute resolution process, even after the decision is made. Furthermore, there is no control over this part of the AB or the WTO as it cannot enforce the decision made through the proceedings. This has resulted in the prescribed “reasonable” period (typically 15 months or less) being exceeded by the losing defendant. Additionally, these WTO rules have been exploited by the disputing governments that arrange compensations or reach settlements in compliance of the WTO rules, without oversight of the WTO. One such matter was the compliance with the WTO ruling by the EU in the banana dispute was delayed until 2006 by the mutual agreement of the US and Ecuador and removed the case from WTO agenda even before the compliance.

Such post-decision negotiations among the disputing parties are another important flexibility afforded by the WTO rules. The opportunity for dispute resolution even after compliance has resulted in the development of system whereby the DSU has generated higher rates of “compliance” which would not have been possible if the rulings had been binding. This is the reason that in the majority of the decided cases, the compliance was not partial or in an untimely manner. This makes the post-decision negotiation “binding” which is vastly different from other prototypical legal realm.

The examination shows a worrying trend in the for the timely compliance of the decisions. In this regard, GATT and “Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights” (TRIPS) cases show timely compliance.[8] The exception involve the two TRIPS cases against the US[9] and the European Communities Bananas[10] case.[11] So, GATT and TRIPS cases have mostly seen desired results. Textile and safeguard cases also showed timely compliance typically. However, this was in the presence of contested measures.[12] Even if the compliance was timely, the whole process took so long that it had become meaningless.[13] Modification of measure has been seen in 75% of trade remedy cases, but the applied duty of 50% has seldomly been changed.[14] Trade remedy cases have proven to be time taking, and almost 50 percent of the Article 21.5 compliance proceedings were trade remedy cases.[15] Modifications and compliance disputes were also common in subsidy, agriculture, and Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) cases.[16] Thus, compliance is not timely in such cases and without any much practical effect.

The analysis of the cases show that only 60% show timely compliance,[17] with “trade remedies, subsidies, agriculture, and SPS” being the problem areas.[18] US, the EU, Canada, Japan, and Australia were among the countries that failed in timely compliance.[19] The cases not complied with were often against each other.[20] Their on-time implementation rate was 50%.[21] Time implemental rate was 80% in the developing countries.[22] The initial trends in regards to the treatment of decision has persisted through the passage of time, even if the cases presented are mostly trade related,[23] and the main source untimely decision implementation is the US. In this regard, the US has reported monthly to the AB on its failure to implement the decision for multiple years in three cases.[24]

The report on timely compliance shows the time to be exceeded by many month with high rates in Article 21.5 compliance proceedings.[25] The AB, on average, issues report within ninety days of an appeal,[26] the overall process takes too long.[27] This is the fact while disregarding the time taken by the proceedings.[28] As such, on surface, the record of the DSU proceedings has been admirable, there is room for improvement, as these concerns have also been raised by businesses.[29] This may be achieved through compensation that can resolve the issue of non-compliance to a large extent. Negotiation option is available in lieu of retaliation for twenty days on expiration of the reasonable period.[30] Though used seldomly, this option has been used in some cases as well.[31] But it is arguable whether more use of compensation is desirable and what benefits it can offer.[32]

European Union:

EU is one of the leading models of international collaboration that established in its nascent form as European Economic Community and The European Coal and Steel Community following the end of the Second World War that had left the Europe in ruins. In order to compete with the global powers and build up the infrastructure to enhance economic development, EU tracks the series of efforts undertaken to integrate the European Community to form a block that could provide synergy in utilization of resources.[33] The establishment of the EU law and the EU’s Court of Justice marks the legal milestone of European legal integration that presented the law and the forum as an overarching body that had the say of final instance in international disputes among the Member States. This presented a unique framework where uniform rules for international trade were developed that presented certainty and autonomy to contracting parties in trade and presented rules that could be used to settle disputes under its jurisdictions.[34]

Post-Keck:

The CJEU judgment in the case of Keck and Mithouard and the implications it has had on the topic of free movement of goods and trade has been a recurrent theme in recent scholarly debate.[35] The judgement in this case has led to huge discourse regarding the development of “tests” or judicial techniques that could help in the interpretation of the Article 34 of the TFEU. In addition, it has also resulted in dispute over the defining qualification of a measure having equivalent effect to a quantitative restriction (MEQR). The most important case law in determining the judicial process of the AB was Dassonville and Cassis de Dijon. This case law established the far reaching principles that expanded across all four freedoms and have been applied by the court ever since which also takes into account any justification to the obstacle to the trade in question by means of an imperative or mandatory requirement applied “in a proportionate manner, i.e. appropriate, necessary and reflecting the (lack of) equivalence of the regulatory framework in place in the country of origin.[36]

The proportionality test was the first legal technique developed by the CJEU to accommodate the growing need for trade freedom and increased pressure for regulation of the Member State’s policy space. The approach was developed based on the balancing approach that sought to reconcile the conflicting interest of all the parties through proportionality test. However the CJEU had adobted a choice of avoidance technique that did not seek full balancing of various affected interest in favour of the principle of parallelism or equivalence where the import or the host state had the burden to provide that the regulatory framework was not functionally equivalent. This was accompanied by the developing presumption that if a specific public interest is taken into account by the legislation of the state of the origin of the product (home state).[37] An overboard implementation of the article 34 was followed due to the joint operation of the presumption of “functional parallelism/principle of equivalence” and the broad interpretation of the notion of obstacle to trade that acted against any national measure affecting intra-EU trade. This problem was highlighted in the criticism of the CJEU’s the Sunday Trading case law.[38]

The development of the balancing approach as discussed above became too wide in scope while implementing the freedom of trade under Article 34 of the TFEU that it introduced too much restriction on the policy making ability of the Member States and resulted in political backlash. To protect the judicial integrity and its regulatory policy space, the CJEU was then forced to consider other tests and approaches and develop other techniques to limit the scope of balance approach. In this regard, “quantitative (de minimis) threshold for significant impediments to cross-border trade” was envisages by the CJEU but was, in the end, abandoned due to the contingent complications.[39] The court later turned to the developed of a qualitative threshold that depended on the causation principles to exclude trade restrictions that are “too uncertain and indirect”.[40]

Categorization:

One of the main avenues that had been a huge topic of debate for the progress is development of legal principles in the CJEU is the development and the progressive demise of the legal categorization approach that had been contributed by the proceedings in the Keck case law. This approach was followed by the explanation under the law for the rules in determining what would be regarded as an obstacle to trade which were presented under Article 34 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union that had the implication of abandoning the “disparate market access” approach introduced by the Keck case law in favour of a more inclusive re-interpretation of the market access rules.

The implications of Keck were no less than a “revolution” that had its own admirers and critics and led to an effort made by the CJEU to define new principles to define new legal categories and also define their boundaries.[41] It also led to the development and research into the efforts for market integration and internal market project architecture that had been the goal for the establishment of the EU. Yet, with the passage of time, and development of better legal principles, the Keck era has come to an end. This is evidence by the CJEU return to a broader definition of Measure Equivalent Quantity Restriction that utilized “market access” notion which focused on balancing of conflicting interests and values rather than legal categorization.

One of the major hurdles in develop the interpretation of the Article 34 of the TFEU for the CJEU is reaching an appropriate balance that would not limit the Member State’s ability to control their own economy and would not disrupt other policy objectives in favour of trade promotion. In this regard, the CJEU’s Keck and Mithouard case law is an important milestone. The case introduced a new legal approach, called legal “categorization”[42] in its balancing approach to limit the courts objective of promotion of trade alone. “Categorization” approach is an alternative to balancing approach that focuses on the dispute resolution through facts classification into exiting legal categories. This redefines the boundaries of existing legal categories or the creation of new ones. As Sullivan[43] put it:

“Categorization and balancing each employ quite different rhetoric. Categorization is the taxonomist’s style-a job of classification and labeling. When categorical formulas operate, all the important work in litigation is done at the outset. Once the relevant right and mode of infringement have been described, the outcome follows, without any explicit judicial balancing of the claimed right against the government’s justification for the infringement. Balancing is more like grocer’s work (or Justice’s)—the judge’s job is to place competing rights and interests on a scale and weigh them against each other. Here the outcome is not determined at the outset, but depends on the relative strength of a multitude of factors.”

Barak argued that the main difference between legal categorization and proportionality is that the latter focuses on a specific balancing conduct.

“Methodologically speaking, thinking in legal categories stands in sharp contrast to legal thinking based upon specific, or ad hoc, balancing … The focus on categories was meant, among others, to prevent the use of specific balancing in each case. The characterization of a set of facts as being attributed to a certain category led to a legal solution, without the need to conduct a specific balancing within that category … once the contours of the category … are determined, there is no room for additional balancing.”[44]

The objective of the categorization approach was to limit the effort of the CJEU in balancing the other public policy objectives of the Member States with the value of trade to judge the limiting factors imposed by the state. This was achieved by developing specific categories to classify the evidential and substantive legal presumptions. Even before the addition of Kick, the CJEU had been applying the categorization principle to separate discriminatory measures from that of indistinctly applicable measures that had been proposed by the European Commission in 1970,[45] which defined the “dichotomy between measures relating to product requirements and selling arrangements.”[46] As such, Keck was not the first instance that the court had applied the categorization approach.

Another contribution imposed by Keck was to restrict the Member State in restricting the trade of goods by defining the principles for the qualification of restrictive measures designed to raise boundaries and obstacles to trade as prohibited by the Article 34 of TFEU. The CJEU opted to adopt an approach focusing on the disparate impact of domestic measure of the Member States to promote domestic goods in favour of the foreign products. The plaintiffs were required by the CJEU to show that the measures undertaken by the Member States, in this regard, were discriminatory, either in fact or in law, to the access of the imported goods to the market. It was also explained by the CJEU that the prohibition of “discrimination in fact” precluded any measure that would be “by nature such as to prevent the imported goods access to the market or to impede access any more than it impedes the access of domestic products.”[47] Even in the post-Keck case laws, the court has used the term of “market access” to determine the MEQR, which has been a controversial approach due to the fact that the court has failed to properly define the term clearly in any of the case laws.[48]

Comity:

One of the most important and interesting application in relation to the international law is the invocation of comity. The of invocation of comity in domestic courts is to limit the national judges in their exercise of jurisdiction over foreign acts or judgements. However, its application is rarely granted as the judges seek to uphold the respect and jurisdiction of the international agreements and relationships through the application of comity. The same result may also be achieved through the application of the “act of state” doctrine[49]. The most common place for the application of comity is instead in disrupting the course of a parallel dispute, which include the declaration of invalidity for arbitration agreement or the request of anti-suit injunctions. An example of such action is the case of Enercon GmbH v Enercon (India) Ltd[50] where the proceedings were brought in front of the English High Court of Justice in order to disrupt the proceedings for the decision of the chair of arbitration that were undertaken by the Bombay High Court. As such, the complications of the procedural tactics by the claimant led to the English court deciding that it would be “inappropriate for this court to seek to go on to determine (the seat of arbitration) in parallel to the (Bombay High Court) or to seek to beat the BHC to the punch in deciding that issue: comity requires the English court in these circumstances to leave the issue to the Indian courts and to stay any consideration by it of that issue in the meantime”.

The same principle maybe used in the legal proceedings that were undertaken by the International court under the public international Law and “perhaps with greater force.”[51] The reason for such malalignment of the rules and jurisdiction is due to the increasing “fragmentation of substantive normative regimes and proliferation of internal legal institutions, occasions for conflict and lack of coordination abound.”[52] However, the efforts undertaken for the increased coordination cannot be disregarded as these are increasingly more rooted in the system of general international law. Application of comity may also be regarded as effort as it can serve to appease the externalities caused by the system decentralisation.

This is one of the obstacles in the implementation of the international law. Though, the application of the principle of comity is far less overreaching in the context of the EU law due to the highly collaborative environment. The regulatory efficiency and the collaboration from the Member States have made the EU legislative system for the dispute resolution to be quite appealing especially due to the development of legal principles that promote certainty in legal proceedings, though some exceptions do exist in the form of defiant member states like Poland and Hungary.[53]

CONCLUSION:

As seen in the discussion undertaken above, both international bodies, EU’s Court of Justice and the WTO govern the commercial disputes in international trade agreements. However, the mechanisms and the rule of law in regards to jurisdiction and enforcement for the both forums is quite different. Critically speaking, the model adopted and presented by the WTO in their dispute resolution process is both efficient and consistent in meeting the objectives. Whereas the political intervention and constraints imposed on the WTO and lack of enforcement ability in critical areas of disputes has led to the once promising forum being relegated to an afterthoughts that has failed to reform the international trade and accelerate international collaboration on fair grounds. As such, the more objective and rule-based approach as adopted by the EU has served to be a more sustainable and consistent international legal system for dispute settlement. This, however, does not discredit the existence and effort undertaken by the WTO, however, limited enforcement power and limitations imposed on it in regards to its application leaves much to be desired.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

LIST OF REFERENCES:

A. Barak, Proportionality: Constitutional Rights and their Limitations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp.508–509.

A.G. Jacobs, Leclerc-Siplec v TF1 Publicité SA (C-412/93) [1995] E.C.R. I-179; [1995] 3 C.M.L.R. 422

Amy Man, Treaties and conventions, (2014), Westlaw

Appellate Body Report, United States-Section 211 Omnibus Appropriations Act of 1998, WT/DS176/AB/R (Jan. 2, 2002)

Appellate Body Report, European Communities- Regime for the Importation, Sale and Distribution of Bananas, WT/DS27/AB/R (Sept. 9, 1997).

Appellate Body, Annual Report for 2007, 42-47, WT/AB/9 (Jan. 30, 2008) [hereinafter Appellate Body 2007 Annual Report].

Appellate Body Report, United States- Subsidies on Upland Cotton, Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by Brazil, WT/DS267/AB/RW (June 2, 2008)

C. Barnard, “Sunday Trading: a Drama in Five Acts” (1994) 57 M.L.R. 449.

D. Doukas, “Untying the Market Access Knot: Advertising Restrictions and the Free Movement of Goods and Services” (2006–07) 9 C.Y.E.L.S. 177

Daniel Pruzin, Mexico Presents ‘Radical’ Proposal for WTO Dispute Resolution Reform, 19 INT’L TRADE REP. (BNA) 1984, 1984 (2002).

Dimitry Kochenov, “Rule of law as a tool to claim supremacy.” (2020).

Dispute Settlement Body, Minutes of Meeting Held in the Centre William Rappard on March 14, 2008, 11 1-50, WT/ DSB/M/248 (Apr. 30, 2008) (discussing Appellate Body Report, United States- Continued Dumping and Subsidy Offset Act of 2000, WT/DS217/AB/R, WT/DS234/AB/R (Jan. 16, 2003) (adopted Jan. 27, 2003)

Dispute Settlement Body, Annual Report (2007), Addendum, Overview of the State of Play of WTO Disputes, 92-95, WT/DSB/43/Add.1 (Dec. 7, 2007) [hereinafter DSB Annual Report (2007)].

E. Spaventa, “The Outer Limit of the Treaty Free Movement Provisions: Some Reflections on the Significance of Keck, Remoteness and Deliège” in C. Barnard and O. Odudu, The Outer Limits of European Union Law (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2009), pp.245–271

Evaluating WTO Dispute Settlement, supra note 4, at 137-38 (discussing countryby-country implementation as of December 2004).

Filippo Fontanelli, Comity, (2016). Westlaw

G. Davies, “Understanding market access: exploring the economic rationality of different conceptions of free movement law” (2010) 11 German Law Journal 671

Gary G. Yerkey, U.S. Poultry Producers Do Not Plan to Urge U.S. to File Case at WTO over EU Import Ban, INT’L TRADE DAILY (BNA), June 9, 2008 (noting EU failure to comply in the Hormones case).

Gregory Shaffer, “What’s new in EU trade dispute settlement? Judicialization, public–private networks and the WTO legal order.” Journal of European Public Policy 13, no. 6 (2006): 832-850.

J. Snell, “The Notion of Market Access: A Concept or a Slogan?” (2010) 47 C.M.L. Rev. 437

J. Weiler, “Constitution of the Common Market Place: Text and Context in the Evolution of the Free Movement of Goods” in P. Craig and G. de Búrca (eds), The Evolution of EU Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), p.349

Judith Goldstein, Miles Kahler, Robert O. Keohane, and Anne-Marie Slaughter. “Introduction: Legalization and world politics.” International organization 54, no. 3 (2000): 385-399.

L. Azoulai (ed.), L’entrave dans le droit du marché interieur (Brussels: Bruylant, 2011); C. Barnard, “Restricting Restrictions: Lessons for the EU from the US?” (2009) 68 Cambridge L.J. 575

Leo Tindemans, European Union. Ministry Of Foreign Affairs, External Trade And Cooperation In Development, (1976).

Lianos, “Shifting Narratives in the European Internal Market” (2010) 21 E.B.L. Rev.705.

Lisa Conant, “The Court of Justice of the European Union.” The Palgrave Handbook of EU Crises. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, (2021). 277-295.

K. Sullivan, “Post-liberal Judging: The Role of Categorization and Balancing” (1992) 63 University of Colorado Law Review 293.

M. Jannson and H. Kalimo, “De minimis meets ‘Market Access’: Transformation in the Substance—and the Syntax—of EU Free Movement Law?” (2014) 51 C.M.L. Rev. 523

Monika Bütler, and Heinz Hauser. “The WTO dispute settlement system: A first assessment from an economic perspective.” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 16, no. 2 (2000): 503-533.

N. Bernard, “Flexibility in the European Single Market” in C. Barnard and J. Scott (eds), The Law of the Single European Market: Unpacking the Premises (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2002), pp.101–122 at pp.104–105.

Nic Shuibhne, The Coherence of EU Free Movement Law (2013), pp.157–188.

P. Eeckhout, “Recent Case Law on Free Movement of Goods: Refining Keck and Mithouard” (1998) E.B.L. Rev. 267.

P. Oliver, “Some further Reflections on the Scope of Article 28–30 (ex 30–36) EC” (1999) 36 C.M.L. Rev. 783, 788–789

Panel Report, United States-Section 110(5) of the US Copyright Act, WT/DS160/R (June 15, 2000) (adopted July 27, 2000)

Panel Report, United States-Laws, Regulations and Methodology for Calculating Dumping Margins (“Zeroing”), Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by the European Communities, WT/DS294/RW (Dec. 17, 2008)

Panel Report, United States-Measures Affecting the Cross-Border Supply of Gambling and Betting Services, Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by Antigua and Barbuda, WT/DS285/RW (Mar. 30, 2007)

S. Weatherill, “After Keck: Some Thoughts on How to Clarify the Clarification” (1996) 33 C.M.L. Rev. 885

Sullivan, “Post-liberal Judging” (1992) 63 University of Colorado Law Review 293.

William J. Davey “Compliance problems in WTO dispute settlement.” Cornell Int’l LJ 42 (2009): 119.

William J. Davey, Expediting the Panel Process in WTO Dispute Settlement, in THE WTO: GOVERNANCE, DISPUTE SETTLEMENT & DEVELOPING COUNTRIES 409, 415-18, 420-21 (Merit E. Janow, Victoria Donaldson & Alan Yanovich eds., 2008) [Expediting the Panel Process].

William J. Davey, Implementation Of The Results Of WTO Remedy Cases, In THE WTO TRADE REMEDY System: EAST Asian Perspectives 33, 33-61 (Mitsuo Matsushita Et Al. Eds., 2006).

WTO Secretariat, Update of WTO Dispute Settlement Cases, 77-78, WT/DS/OV/33 (June 3, 2008) (discussing how Japan requested the creation of an Article 21.5 panel to resolve compliance issues of United States-Zeroing (Japan)).

Yuval Shany, The competing jurisdictions of international courts and tribunals. Vol. 418. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

LIST OF CASES:

Agreement Under Article 21.3(b) of the DSU, United States- Definitive Safeguard Measures on Imports of Circular Welded Carbon Quality Line Pipe from Korea, WT/DS202/18 (July 31, 2002) (the United States provided trade compensation to Korea)

Aklagaren v Mickelsson and Roos (C-142/05) [2009] E.C.R. I-4273; [2009] All E.R. (EC) 842 )

Commission v Italy (C-110/05) [2009] E.C.R. I-519; [2009] 2 C.M.L.R. 34 at [56].

Criminal Proceedings against Bluhme (C-67/97) [1998] E.C.R. I-8033; [1999] 1 C.M.L.R. 612 at [22]

Criminal Proceedings against Burmanjer (C-20/03) [2005] E.C.R. I-4133; [2006] 1 C.M.L.R. 24 at [31])

Criminal Proceedings against Peralta (C-379/92) [1994] E.C.R. I-3453 at [24]

Enercon GmbH v Enercon (India) Ltd [2012] EWHC 3711 (Comm)

Procureur du Roi v Benoît and Gustave Dassonville (8/74) [1974] E.C.R. 837; [1974] 2 C.M.L.R. 436 at [5]

Rewe-Zentral AG v Bundesmonopolverwaltung für Branntwein (Cassis de Dijon) (120/78) [1979] E.C.R. 649; [1979] 3 C.M.L.R. 494 at [8]–[11] and [14]–[15].

Mutually Acceptable Solution on Modalities for Implementation, Japan Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages, WT/DS8/20, WT/DS10/20, WT/DS11/18 (Jan. 12, 1998) (Japan provided trade compensation to Canada);

R. (on the application of Khan) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2014] EWCA Civ 24; [2014] 1 W.L.R. 872

LIST OF LEGISLATION:

GATT Secretariat 1994.

Directive 70/50 on the abolition of measures which have an effect equivalent to quantitative restrictions on imports and are not covered by other provisions adopted in pursuance of the EEC Treaty [1970] OJ L13/29 .

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties 1969

Notification of Mutually Acceptable Solution, Turkey- Restrictions on Imports of Textile and Clothing Products, WT/DS34/14 (july 19, 2001) (Turkey provided trade compensation to India)

Notification of a Mutually Satisfactory Temporary Arrangement, United States-Section 110(5) of the US Copyright Act, WT/DS160/23 (June 26, 2003) (the United States provided monetary compensation for three years of non-implementation).

[1] art.2 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties 1969

[2] Amy Man, Treaties and conventions, (2014), Westlaw

[3] Filippo Fontanelli, Comity, (2016). Westlaw

[4] The full name is the “Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes” (hereinafter “DSU”). For the complete text of the DSU and other Uruguay Round agreements, see GATT Secretariat 1994.

[5] Goldstein, Judith, Miles Kahler, Robert O. Keohane, and Anne-Marie Slaughter. “Introduction: Legalization and world politics.” International organization 54, no. 3 (2000): 385-399.

[6] Shaffer, Gregory. “What’s new in EU trade dispute settlement? Judicialization, public–private networks and the WTO legal order.” Journal of European Public Policy 13, no. 6 (2006): 832-850.

[7] Shaffer, Gregory. “What’s new in EU trade dispute settlement? Judicialization, public–private networks and the WTO legal order.” Journal of European Public Policy 13, no. 6 (2006): 832-850.

[8] Evaluating WTO Dispute Settlement, supra note 4, at 114-15, 139-40.

[9] Appellate Body Report, United States-Section 211 Omnibus Appropriations Act of 1998, WT/DS176/AB/R (Jan. 2, 2002) [hereinafter US-Section 211 Appropriations Act]; Panel Report, United States-Section 110(5) of the US Copyright Act, WT/DS160/R (June 15, 2000) (adopted July 27, 2000) [hereinafter US-Section 110(5) Copyright Act].

[10] Appellate Body Report, European Communities- Regime for the Importation, Sale and Distribution of Bananas, WT/DS27/AB/R (Sept. 9, 1997).

[11] Evaluating WTO Dispute Settlement, supra note 4, at 115, 140. The two cases in which the United States has been found to have violated the TRIPS Agreement required Congressional action for implementation, which has not been forthcoming. ibid. at 115. The prevailing party in the two cases, the European Union, has never sought authority to retaliate, perhaps because the cases involve a relatively limited amount of trade.

[12] ibid. at 110.

[13] ibid. at 113-14.

[14] William J. Davey, Implementation Of The Results Of WTO Remedy Cases, In THE WTO TRADE REMEDY System: EAST Asian Perspectives 33, 33-61 (Mitsuo Matsushita Et Al. Eds., 2006).

[15] Dispute Settlement Body, Annual Report (2007), Addendum, Overview of the State of Play of WTO Disputes, 92-95, WT/DSB/43/Add.1 (Dec. 7, 2007) [hereinafter DSB Annual Report (2007)].

[16] ibid.: Evaluating WTO Dispute Settlement, supra note 4, at 114-15, 139-40.

[17] Evaluating WTO Dispute Settlement, supra note 4, at 137-38 (discussing countryby-country implementation as of December 2004).

[18] Ibid. at 114.

[19] ibid. at 113, 138.

[20] ibid

[21] ibid

[22] ibid

[23] See Appellate Body, Annual Report for 2007, 42-47, WT/AB/9 (Jan. 30, 2008) [hereinafter Appellate Body 2007 Annual Report].

[24] See, e.g., Dispute Settlement Body, Minutes of Meeting Held in the Centre William Rappard on March 14, 2008, 11 1-50, WT/ DSB/M/248 (Apr. 30, 2008) (discussing Appellate Body Report, United States- Continued Dumping and Subsidy Offset Act of 2000, WT/DS217/AB/R, WT/DS234/AB/R (Jan. 16, 2003) (adopted Jan. 27, 2003) [hereinafter United States- Continued Dumping]; USSection 211 Appropriations Act, supra note 7; US- Section 110(5) Copyright Act, supra note 7). Moreover, there is one case in which the European Union and Japan comment monthly on the failure of the United States to implement or report. ibid. C11 20-45 (discussing United States- Continued Dumping, supra). In addition, the United States has recently lost three Article 21.5 compliance actions. See generally Appellate Body Report, United States- Subsidies on Upland Cotton, Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by Brazil, WT/DS267/AB/RW (June 2, 2008); Panel Report, United States-Laws, Regulations and Methodology for Calculating Dumping Margins (“Zeroing”), Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by the European Communities, WT/DS294/RW (Dec. 17, 2008); Panel Report, United States-Measures Affecting the Cross-Border Supply of Gambling and Betting Services, Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by Antigua and Barbuda, WT/DS285/RW (Mar. 30, 2007) [hereinafter US-Gambling]. Another compliance action is pending against the United States as well. See WTO Secretariat, Update of WTO Dispute Settlement Cases, 77-78, WT/DS/OV/33 (June 3, 2008) (discussing how Japan requested the creation of an Article 21.5 panel to resolve compliance issues of United States-Zeroing (Japan)).

[25] William J. Davey, Expediting the Panel Process in WTO Dispute Settlement, in THE WTO: GOVERNANCE, DISPUTE SETTLEMENT & DEVELOPING COUNTRIES 409, 415-18, 420-21 (Merit E. Janow, Victoria Donaldson & Alan Yanovich eds., 2008) [Expediting the Panel Process].

[26] ibid. at 418

[27] d. at 419-20.

[28] ibid. at 421-30

[29] See, e.g., Gary G. Yerkey, U.S. Poultry Producers Do Not Plan to Urge U.S. to File Case at WTO over EU Import Ban, INT’L TRADE DAILY (BNA), June 9, 2008 (noting EU failure to comply in the Hormones case). In the DSU reform negotiations, Mexico has been particularly critical of what it calls the “‘fundamental problem’ of the WTO dispute settlement system, namely the ‘period of time which a WTO-inconsistent measure can be in place without the slightest consequences’ to the offending party.” Daniel Pruzin, Mexico Presents ‘Radical’ Proposal for WTO Dispute Resolution Reform, 19 INT’L TRADE REP. (BNA) 1984, 1984 (2002).

[30] DSU art. 22.1-22.2.

[31] Generally, compensation has been used when certain implementing measures have been delayed beyond the end of the reasonable period of time set for implementation. See, e.g., Mutually Acceptable Solution on Modalities for Implementation, JapanTaxes on Alcoholic Beverages, WT/DS8/20, WT/DS10/20, WT/DS11/18 (Jan. 12, 1998) (Japan provided trade compensation to Canada); Notification of Mutually Acceptable Solution, Turkey- Restrictions on Imports of Textile and Clothing Products, WT/DS34/14 (july 19, 2001) (Turkey provided trade compensation to India); Agreement Under Article 21.3(b) of the DSU, United States- Definitive Safeguard Measures on Imports of Circular Welded Carbon Quality Line Pipe from Korea, WT/DS202/18 (July 31, 2002) (the United States provided trade compensation to Korea); Notification of a Mutually Satisfactory Temporary Arrangement, United States-Section 110(5) of the US Copyright Act, WT/DS160/23 (June 26, 2003) (the United States provided monetary compensation for three years of non-implementation).

[32] William J. Davey “Compliance problems in WTO dispute settlement.” Cornell Int’l LJ 42 (2009): 119.

[33] Leo Tindemans, European Union. Ministry Of Foreign Affairs, External Trade And Cooperation In Development, (1976).

[34] Lisa Conant, “The Court of Justice of the European Union.” The Palgrave Handbook of EU Crises. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, (2021). 277-295.

[35] See, L. Azoulai (ed.), L’entrave dans le droit du marché interieur (Brussels: Bruylant, 2011); C. Barnard, “Restricting Restrictions: Lessons for the EU from the US?” (2009) 68 Cambridge L.J. 575; G. Davies, “Understanding market access: exploring the economic rationality of different conceptions of free movement law” (2010) 11 German Law Journal 671; D. Doukas, “Untying the Market Access Knot: Advertising Restrictions and the Free Movement of Goods and Services” (2006–07) 9 C.Y.E.L.S. 177; P. Eeckhout, “Recent Case Law on Free Movement of Goods: Refining Keck and Mithouard” (1998) E.B.L. Rev. 267.

[36] Procureur du Roi v Benoît and Gustave Dassonville (8/74) [1974] E.C.R. 837; [1974] 2 C.M.L.R. 436 at [5]; and Rewe-Zentral AG v Bundesmonopolverwaltung für Branntwein (Cassis de Dijon) (120/78) [1979] E.C.R. 649; [1979] 3 C.M.L.R. 494 at [8]–[11] and [14]–[15].

[37] On the different interpretations of this principle, see J. Weiler, “Constitution of the Common Market Place: Text and Context in the Evolution of the Free Movement of Goods” in P. Craig and G. de Búrca (eds), The Evolution of EU Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), p.349; N. Bernard, “Flexibility in the European Single Market” in C. Barnard and J. Scott (eds), The Law of the Single European Market: Unpacking the Premises (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2002), pp.101–122 at pp.104–105.

[38] See, C. Barnard, “Sunday Trading: a Drama in Five Acts” (1994) 57 M.L.R. 449.

[39] Opinion of A.G. Jacobs, Leclerc-Siplec v TF1 Publicité SA (C-412/93) [1995] E.C.R. I-179; [1995] 3 C.M.L.R. 422 . See S. Weatherill, “After Keck: Some Thoughts on How to Clarify the Clarification” (1996) 33 C.M.L. Rev. 885. See also, more recently, M. Jannson and H. Kalimo, “De minimis meets ‘Market Access’: Transformation in the Substance—and the Syntax—of EU Free Movement Law?” (2014) 51 C.M.L. Rev. 523. The Court nevertheless decided to abandon that route in Officier van Justitie v Van de Haar and Kaveka de Meern BV (177 and 178/82) [1984] E.C.R. 1797; [1985] 2 C.M.L.R. 566 , although the terminology “insignificant effects” appears in some cases (see Criminal Proceedings against Burmanjer (C-20/03) [2005] E.C.R. I-4133; [2006] 1 C.M.L.R. 24 at [31]) and to a certain extent one may claim that the emphasis put by the recent case law of the CJEU on the “considerable” influence exercised by the national measure on the behaviour of consumers may amount to some form of de minimis criterion: see Commission v Italy (C-110/05) [2009] E.C.R. I-519; [2009] 2 C.M.L.R. 34 at [56].

[40] See H. Krantz GmbH & Co v Ontvanger der Directe Belastingen (C-69/88) [1990] E.C.R. I-583; [1991] 2 C.M.L.R. 677 at [11]; Criminal Proceedings against Peralta (C-379/92) [1994] E.C.R. I-3453 at [24]; Criminal Proceedings against Bluhme (C-67/97) [1998] E.C.R. I-8033; [1999] 1 C.M.L.R. 612 at [22]. On “remoteness” and its links with Keck , see P. Oliver, “Some further Reflections on the Scope of Article 28–30 (ex 30–36) EC” (1999) 36 C.M.L. Rev. 783, 788–789; E. Spaventa, “The Outer Limit of the Treaty Free Movement Provisions: Some Reflections on the Significance of Keck, Remoteness and Deliège” in C. Barnard and O. Odudu, The Outer Limits of European Union Law (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2009), pp.245–271; Nic Shuibhne, The Coherence of EU Free Movement Law (2013), pp.157–188.

[41] See, for instance, Verein gegen Unwesen in Handel und Gewerbe Köln eV v Mars GmbH (C-470/93) [1995] E.C.R. I-1923; [1995] 3 C.M.L.R. 1 (on the distinction between pure selling arrangements and marketing methods employed by the trader that affect the nature, composition or packaging of the good, which are treated as product requirement rules) or the more recent case law of the CJEU implicitly distinguishing restrictions on the use of products from the Keck categories (see, for instance, Aklagaren v Mickelsson and Roos (C-142/05) [2009] E.C.R. I-4273; [2009] All E.R. (EC) 842 ), although one may also advance the view, as I will do in the remainder of this study, that the Court seems to have used this case law in order to revisit the scope of art.34 TFEU and to implicitly abandon the legal categorisation approach inaugurated in Keck .

[42] See K. Sullivan, “Post-liberal Judging: The Role of Categorization and Balancing” (1992) 63 University of Colorado Law Review 293. On the distinction between “categorization” and “balancing” as techniques for limiting “judicial legislation” and, in our case, also the extension of the scope of negative integration.

[43] Sullivan, “Post-liberal Judging” (1992) 63 University of Colorado Law Review 293.

[44] A. Barak, Proportionality: Constitutional Rights and their Limitations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp.508–509.

[45] Directive 70/50 on the abolition of measures which have an effect equivalent to quantitative restrictions on imports and are not covered by other provisions adopted in pursuance of the EEC Treaty [1970] OJ L13/29 .

[46] Criminal proceedings against Keck and Mithouard (Keck) (C-267/91 and C-268/91) [1993] E.C.R. I-6097; [1995] 1 C.M.L.R. 101 at [16].

[47] Keck (C-267/91 and C-268/91) [1993] E.C.R. I-6097 at [17].

[48] For a discussion, J. Snell, “The Notion of Market Access: A Concept or a Slogan?” (2010) 47 C.M.L. Rev. 437; Lianos, “Shifting Narratives in the European Internal Market” (2010) 21 E.B.L. Rev.705.

[49] see R. (on the application of Khan) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2014] EWCA Civ 24; [2014] 1 W.L.R. 872

[50] [2012] EWHC 3711 (Comm)

[51] Yuval Shany, The competing jurisdictions of international courts and tribunals. Vol. 418. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

[52] ibid

[53] Dimitry Kochenov, “Rule of law as a tool to claim supremacy.” (2020).